Opus 4: Iterative vs. Inventive

Along with Roam, Ancient Rivers, Minsky Moments, and Rachmaninoff

We Need Invention, Not Iteration

On Saturday, Marc Andreesen published a rallying cry to the world: “It’s Time To Build.” People are interpreting and reacting to his plea in a few different ways. Some encourage the call to arms and support the post while others are dismissive of this point coming from an investor. There is a bit of hypocrisy behind an investor telling the world we need to build - granted Andreesen built Netscape.

Due to the seemingly endless supply of cash, for the last handful of years, entrepreneurship has had the upper hand in the never-ending dance between labor and capital. This advantage has caused the obscene valuations and perpetual private market investments that gave birth to the Juicero, WeWork, and other companies who promised to “elevate the world’s consciousness” while, in reality, they just iterated on existing technology.

As I wrote back in March, the last two macroeconomic cycles (2001-2008 and 2009-2020) did not invent anything compared to the cycles that preceded them.

The loudest voice in the room regarding this absence of inventive growth is easily Peter Thiel. On Tyler Cowen’s first Conversations interview in 2015, they touched on this exact issue:

There’s the question of stagnation, which I think has been a story of stagnation in the world of atoms, not bits. I think we’ve had a lot of innovation in computers, information technology, Internet, mobile Internet in the world of bits. Not so much in the world of atoms, supersonic travel, space travel, new forms of energy, new forms of medicine, new medical devices, etc. It’s sort of been this two-track area of innovation […]

The relative “easy” route for the past two decades was to iterate on software. Pull-requesting on GitHub is far more comfortable than writing any code from scratch. Leveraging existing Python libraries saves time compared to producing your own. The last revolutionary technology was the smartphone at the start of the decade which became a launching platform for many subsequent iterative technology stacks. The greatest returns over the last decade were driven by the “XaaS” movements. A wider selection of deliverable food and updates to the taxi systems did not drive society forward in any way. Innovation in atoms has all but been abandoned as the hardware companies of our day are D2C beds and baggage.

One of my favorite Thiel heuristics to reference is to look at pictures of homes from the 1960/70s and compared the interiors to those of today. Apart from minor style changes and a flatter TV screen, the living room your parents called home is not too different than yours.

In response to Thiel’s pessimistic words on both Cowen’s podcast and his subsequent appearance at the RNC, John Mannes refuted the claim that the world has slowed down and lost its inventiveness. He goes onto write,

The America of today is building pocket sized satellites, creating spider silk, and designing autonomous vehicles. Since 1968, every state but five has increased its patent output per capita. […]

“Of course, not every patent gets spun up into an invention, and the patent system itself is in need of reform. But university research spending is up, our universities are more diverse, VC investment is up, and public-private partnerships are all the rage.”

Patents per capita are not a measure of progress, and the U.S.A. is behind the pack leaders on this front anyway (side note: Thiel points out in the Cowen interview that Japan is the least mimetic country in the world and it is no coincidence they have the most patents). The vast majority of patents are held by companies that build out a patent armada by slightly iterating on their product that they want to defend. This inorganic creation causes a regulatory wall that competitors cannot fight against. Mannes then points to an increase in VC investment as a marker of creative progress. As Venkatesh tweeted this past week, VCs typically don’t invest in new things, rather, they invest upon patterns they have seen before:

The natural progression of this argument is to point to science (as Mannes did) and say that scientists are still pushing forward with original research. When you abstract away the NPV of research and fund it with grant money and donations, exploratory research should go up because the inherent risk causes no direct downside. Unfortunately, the culture within science has changed due to the incentives changing:

Scientists are measured by concrete metrics that are intended to capture the breadth of their contributions to the scientific enterprise. The rule for research scientists, at least those working in university settings, used to be “publish or perish.” This idea, first articulated in the 1940s, implicitly assumes that a productive scientist publishes many papers while an unproductive scientist publishes few. A variant of this rule involves 8 counting the number of papers published in the most prestigious scientific journals. […]

Because scientists respond to incentives just as everyone else does, the reduction in the reward for novel, exploratory, work has reduced the effort devoted to it in favor of pursuing more incremental science which seeks to advance established ideas. Furthermore, as ideas are not born as breakthroughs—they need the attention and revision of a community of scientists to be developed into transformative discoveries—this decrease in scientists’ willingness to engage in an exploration of new ideas has meant that fewer new ideas have developed into breakthrough ideas. The underlying change in scientist incentives in turn has been driven by the shift toward evaluating each scientist based on how popular their published work is in the scientific community, with popularity measured by the number of times their work is cited by other scientists. We call this shift the ‘citation revolution’.

Scientific success is no longer a measure of discovery but a measure of publishing and subsequent citing of your publishing. My significant other is a researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering and claims there is a palpable directive to publish as much as you can. As touched on in Opus 3, mimetic behavior runs rampant and it seems it has made its way into the research labs - places that were the last standing pillars of novelty and creativeness.

Getting back to Andressen’s piece, it is indeed time to build. But, we need to take actual risks and build new things, weird things, and the things we have been dismissing as too hard or too outlandish. As Venkatesh tweeted, capital allocator pattern matching has forced the builders to stop taking 0 to 1 risk. Any investor that pleads others to start building should first take a look at the word document they have on their computer called “ideas that I would fund” and just go out and start building the ideas on the list. I would start building tomorrow and drop any job I had if I could come up with a good enough idea - ping me if I can join your idea. But, in the meantime, the capital allocators like Marc and myself must stop providing endless capital to the next fabulous CRM or food delivery app and instead allocate to the true builders of change.

Roaming Around Roam

This week’s topic-de-jour (other than Clubhouse) on VC Twitter was Roam Research, a new note-taking app. If your initial reaction was a confused shrug, then you aren’t alone. Having been a long-time user of Evernote, and most recently, Notion, I have never had a 10x experience with any note-taking tools. They are usually built around utility, not user experience.

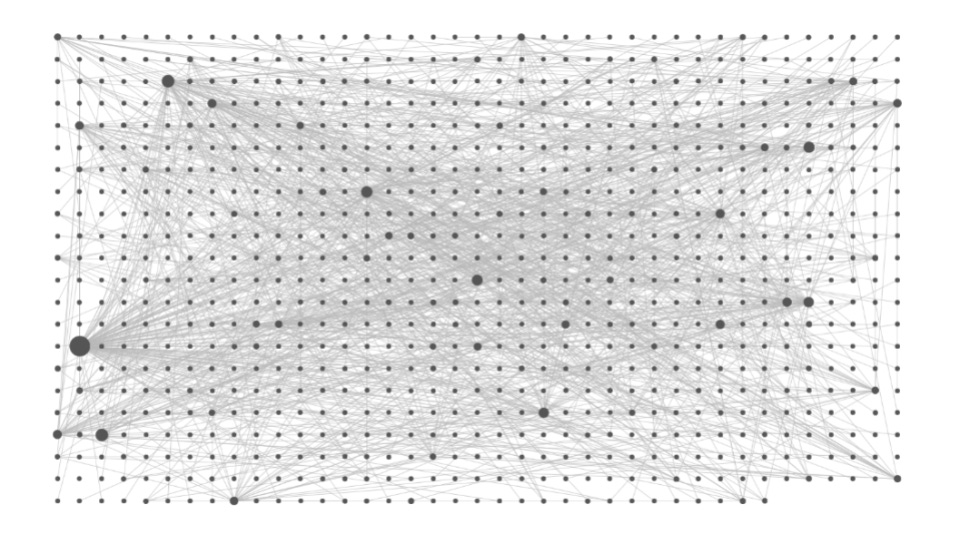

Roam is a bit different. All traditional note apps, and filing systems of any kind, follow a linear, sub-folder structure: Root folder —> Topic Folder —> Sub-Topic Folder. Roam builds out a graph of every topic you write about:

Every subject, idea, name, etc. you write within Roam can have its own node within the graph. The argument being that this bilateral linking is the closest resemblance to our own brain structure. The above image is a visualization of a Roam Research graph with a line between nodes representing a bilateral connection between ideas.

I have been using Roam for a few months now on and off but I am now forcing myself to transfer all note-taking and writing to the platform now that I understand the potential. I encourage everyone to watch a few tutorials on Roam and try it out for yourself.

Homework Reading

A Failure, But Not of Prediction

The general consensus is the media did a terrible job predictively reporting the coronavirus and its effects. Scott Alexander presents an equalizing take on the backlash:

I don’t like this conclusion. But I have to ask myself – if it was so easy, why didn’t I do it? It’s easy to look back and say “yeah, I always secretly knew it would be pretty bad”. I did a few things right – I started prepping half-heartedly in mid-February, I recommended my readers prep in early March, I never criticized others for being alarmist. Overall I give myself a solid B-. But if it was so easy, why didn’t I post “Hey everyone, I officially predict the coronavirus will be a nightmarish worldwide pandemic” two months ago? It wouldn’t have helped anything, but I would have had bragging rights forever. For that matter, why didn’t you post this – on Facebook, on Twitter, on the comments here? You could have gone down in legend, alongside Travis W. Fisher, for making a single tweet. Since you didn’t do that (aside from the handful of you who did – we love you, Balaji) I conclude that predicting it was hard, even for smart and well-intentioned people like yourselves.

What Should We Be Worried About (2013)?

I recently discovered edge.org, which is well known for their annual questions which get responses from the likes of Richard Dawkins, Steven Pinker, etc. The above response from Eric Weinstein regarding the “war on excellence” is an especially interesting answer to the 2013 question:

But such disregard, bordering on deviance and delinquency, was often outweighed by feats of genius and heroism. We have spent the last decades inhibiting such socially marginal individuals or chasing them to drop out of our research enterprise and into startups and hedge funds. As a result our universities are increasingly populated by the over-vetted specialist to become the dreaded centers of excellence that infantilize and uniformize the promising minds of greatest agency.

The downfall of the university has been partly due to them dismissing weird while encouraging consensus.

A decade-old post from Venkatesh that I stumbled across recently is every bit relevant with every economist (armchair or not) trying to figure out what the recovery will look like (U, V, or L-Shaped?). Cash flows need stability in order to have a business organization built on top of them, and when they dry-up, they don’t come roaring back like a dam being let loose. Tepid consumers and heavily indebted businesses have little incentive to go out and restart their old habits of spending. The recovery will not be V-shaped, and it will not be fast. Human behavior has innately changed as a result of the crisis. Risk-taking has all but vanished - see Opus 3 for interest rates post-pandemics.

Organizations are like riverbank communities. They are as old as the last significant course change or waterfront battle. The stability of the river, not the attitudes of people, is what makes old organizations seem set in their ways. Perhaps people resist new ideas not because they have specific personalities, but because they have settled on the banks of a river of money of a certain age. Or perhaps there is self-selection. Possibly the hidebound kinds go settle on the banks of the most ancient rivers. Tax rivers are among the oldest and most stable rivers of money (and the only ones protected by the threat of legitimate force), and people attracted to government work aren’t exactly known for being passionate champions of creative destruction.

Some startups are about finding and colonizing the banks of minor unknown tributaries of old rivers. Others are about creating new rivers. Still others are about building canals between vigorous new rivers and somnolent old ones. And of course, there are those that are about displacing incumbents from prime waterfront locations.

Is Private Equity Having It’s Minsky Moment?

Not much to add here other than reiterating that leveraged private equity is most likely screwed…

Private equity is undergoing what the great theorist Hyman Minsky pointed out is the Ponzi stage of the credit cycle in capitalist financial systems. This is the final stage before a blow-up. As Minsky observed, a period of placidity starts with firms borrowing money but being able to cover their borrowing with cash flow. Eventually, there’s more risk-taking until there’s a speculative frenzy, and firms can’t cover their debts with cash flow. They keep rolling over loans, and just hope that their assets keep going up in value so that they can sell assets to cover loans if necessary. To give an analogy, in 2006, when people in Las Vegas were flipping homes with no income, assuming that home values always went up, that was the Ponzi stage.

Today’s Music: Rachmaninoff - Piano Concerto #2 in C Minor, Op. 18

Following the theme of today’s letter, I thought Rachmaninoff would be an appropriate composer to present. By almost every account, Rachmaninoff was the most inventive, weird, and original classical composer. The tangible epicness of his pieces created an entirely new genre.

Regarding this Piano Concerto, it is allegorical to the above writing as to where the world stands today and where we might be able to go:

This concerto saved Rachmaninoff’s compositional career. In 1897, the premiere of his Symphony No. 1 had gone badly, victim of the fact that the conductor, Alexander Glazunov, was highly intoxicated that evening. Reviews of the performance, and the symphony itself, were so cruel that Rachmaninoff, finding himself crippled with writer’s block, swore off composition in favor of piano performance. Three years later, friends and family persuaded him to consult with Dr. Nicolai Dahl, a pioneer in techniques of hypnotism, and, not incidentally, an avid amateur musician. After months of sessions, Rachmaninoff found again the courage to compose and completed a new concerto, the No. 2 in C Minor. Its premiere was given to great acclaim in Moscow on November 9, 1901, with the composer himself as soloist.

We need more people like Rachmaninoff.

Much like today’s lack of invention, music has lost its itch for change. Music is becoming more and more homogenous in its structure, sound, and length. All modern pop music follows roughly the same chord progressions. Songs are also becoming shorter and shorter, the Rachmaninoff Concerto above is at least 35 minutes played at its fastest pace. Rap music, which once was considered the most innovative form of music back at its birth (~1980-1985), has lost all inventiveness. It used to have meaning, political movements, and collateral behind it. Today, rap artists aren’t even using real words (WARNING: incredibly NSFW and vulgar, but drives home a good point).

The worlds of production and art have both lost their kernels of true creativity. It is interesting that they both lost their ways in the ~1960-70s. I am still working to find the reasons for this parallelism.

We can no longer optimize for short-term gain and profits in lieu of long-term creation and invention. It creates fragile systems that are built on pattern matching and iterating on the status quo.