Programming Note

Apologies for the radio silence from The Opus. The last few weeks have been exceptionally busy, and with all the horrific happenings in the world, my creative thinking has taken a hit.

Introduction

Even after accounting for recency bias, 2020 has been an incredibly important year for the world’s progress in healthcare, public safety, and inequality. Instead of piling onto the many great perspectives out there already, I want to revisit a different year that can explain many of the issues we are experiencing today. That year is 1971.

A Mountain Hotel

Carroll, New Hampshire is a quiet community nestled in the western shadows of the White Mountains. It only has one stoplight governing the main crossroads, US-3 and US-302, around which the town is centered. There are a few cozy lodges and campgrounds on the outer edges of town that house the many summer campers that pass through town each year. The Ammonoosuc River gently winds its way through the town of 763 full-time residents as it makes its way to the Connecticut River many miles west. The Caroll post office, fire department and town hall all sit within line of sight of one another. As you head east out of Carroll on US-302, you can catch a glimpse of Mt. Washington, the highest peak in the northeastern United States, as it towers over the surrounding White Mountains National Forest.

After a few minutes, you will approach the unincorporated establishment of Fabyan. There will be signs at the main intersection to take a left towards the Mt. Washington Cog Railway, a railway built-in 1869 to serve as the primary means of transport for summitting the namesake mountain. As you watch Fabyan fade away in your rearview mirror, you will see a much different site around the corner: The Omni Mount Washington Hotel.

The building is nothing short of magnificent with its Spanish colonial design and grandiose size rising above the surrounding foliage. It is an oasis in the middle of nowhere with a golf course, spas, and more than 200 rooms. To most passing people, the building seems like a mountain retreat for the NYC elite. But, the hotel is one of the most important physical memorials in modern economics and finance.

The Bretton Woods Agreement

In July of 1944, The Omni Hotel was the conference location for the Bretton Woods System. Over 700 delegates from 44 Allied nations converged on this quiet mountain hideout amidst WW2 to rebuild the global financial system that was being brought to its knees. The world wanted to create a new economic order, and it attempted to do so with The Bretton Woods System.

Initially, there was supposed to be an agnostic world currency unit, the bancor as Keynes labeled it, but, the United States objected under the assumption that the USD would be the most reliable anchor and forced the system to adopt the USD as a reserve unit. Unfortunately, while currency plays an integral role in the macroeconomic condition of a country, other factors drive unemployment, inflation, and general flows within the economy. The dollar was acting as the proxy currency for everyone, not just America. As global trade took off, demand for dollars fell, and the global supply increased dramatically with trade balances shifting all while the exchangeable gold supply back in the U.S. only marginally increased. President Johnson’s “Great Society” programs added governmental fuel to the inflation fire as the federal government started to spend billions on domestic policies. As a result, the United States began to see rapid inflation at the start of the 1960s and into the 1970s:

Since countries had to hold USD to peg their currency to, inflation rose around the world even in countries where it economically wasn’t supposed to due to fundamental domestic reasons such as unemployment, slowing consumption, etc.

As global inflation took off,

Michael Bordo explains the final days of the Bretton Woods System well:

After the devaluation of [British] sterling in November 1967, pressure mounted against the dollar via the London gold market. In the face of this pressure, the Gold Pool was disbanded on 17 March 1968 and a two-tier arrangement put in its place. In the following three years, the US put considerable pressure on other monetary authorities to refrain from converting their dollars into gold.

The decision to suspend gold convertibility by President Richard Nixon on 15 August 1971 was triggered by French and British intentions to convert dollars into gold in early August. The US decision to suspend gold convertibility ended a key aspect of the Bretton Woods system. The remaining part of the System, the adjustable peg, disappeared by March 1973.

The world caught onto the fact that the U.S. did not have enough gold in collateral, and an international bank run was about to begin. Knowing he did not have the amount of gold required, Nixon suspended the gold conversion program, and the collateralized peg vanished.

While President Nixon is known for a few other things, his decision on August 15, 1971, would go on to be one of the most impactful decisions ever made by any president.

The Start of The Fiat Experiment

Venkatesh Rao’s “The Great Weirding” has shown that today’s cultural zeitgeist started in May 2016. Today’s economic zeitgeist, on the other hand, all started on August 15, 1971.

While the Federal Reserve was created in 1913 via Wilson’s “Federal Reserve Act”, the monetary body had limited influence of the money system with their discount rate lever due to its tying to gold until 1971. Once Nixon removed the gold peg, the Fed had ultimate control both on the supply and cost of money. This control went beyond the borders of the States since the dollar, while not enforced as so, was still the global reserve currency.

Now that the world was entirely fiat, the monetary policymakers were in the driver’s seat more than ever. Unilateral control vs. market control on economic levers such as money supply and cost of capital is something that has been debated for the entire history of money. But, the fiat experiment has only been running for 50 years and has had some interesting results so far.

Visualizing the sudden change across the economy is an essential part of truly appreciating the implications of this sandbox experiment of fiat money. There is no better, or more efficient, place to do that then the aptly named wtfhappenedin1971.com.

I encourage you to scroll through the site and appreciate the different views of the world and how it changed so drastically since that year - please note some of these effects are unrelated to the Bretton Woods system ending and are results of other social laws being changed. But, I will highlight a few key charts below.

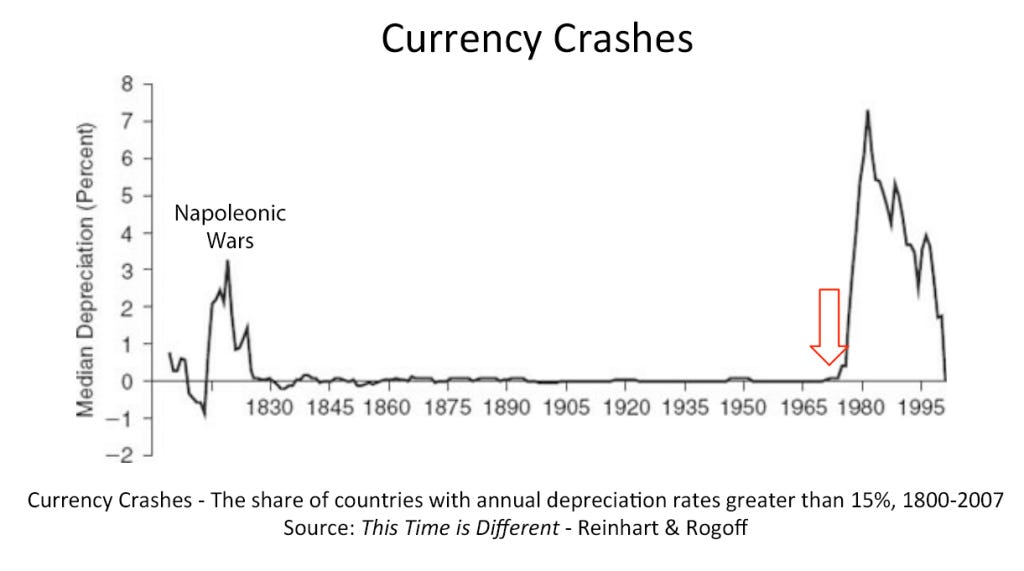

Once the global lock on currency pegs was lifted, nations raced to devalue their free-floating currencies to make their export pricing as attractive as possible. While this is great for trade balances, local purchasing power goes down the drain. Hyperinflation ran rampant as these currency wars proliferated:

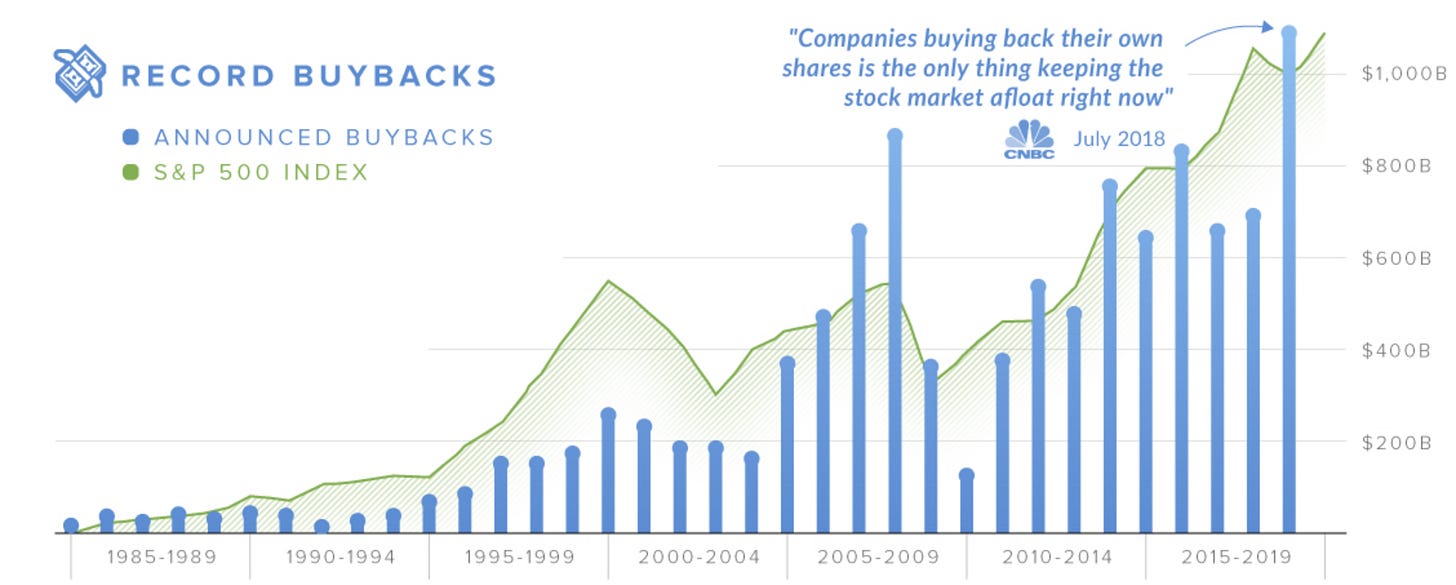

Income inequality also took a u-turn in the early ’80s not directly because of the Bretton Woods System ending but because of a change in the SEC ruling around stock repurchasing. Before 1981, public companies had to disclose the set price, time, and amount of stock that was going to be repurchased by their corporate treasuries. There was also general ambiguity around if this practice was the best use of capital. This law and attitude changed, and since CEO / management compensation is tied to share performance, repurchase programs took off. The top 1% saw a resurgence in their relative wealth as they hold a disproportionate amount of investments. Over the next 50 years, as interest rates marched their way back down from the Volcker stagflation shock, debt capital became cheaper and was being used more and more to go and repurchase stock.

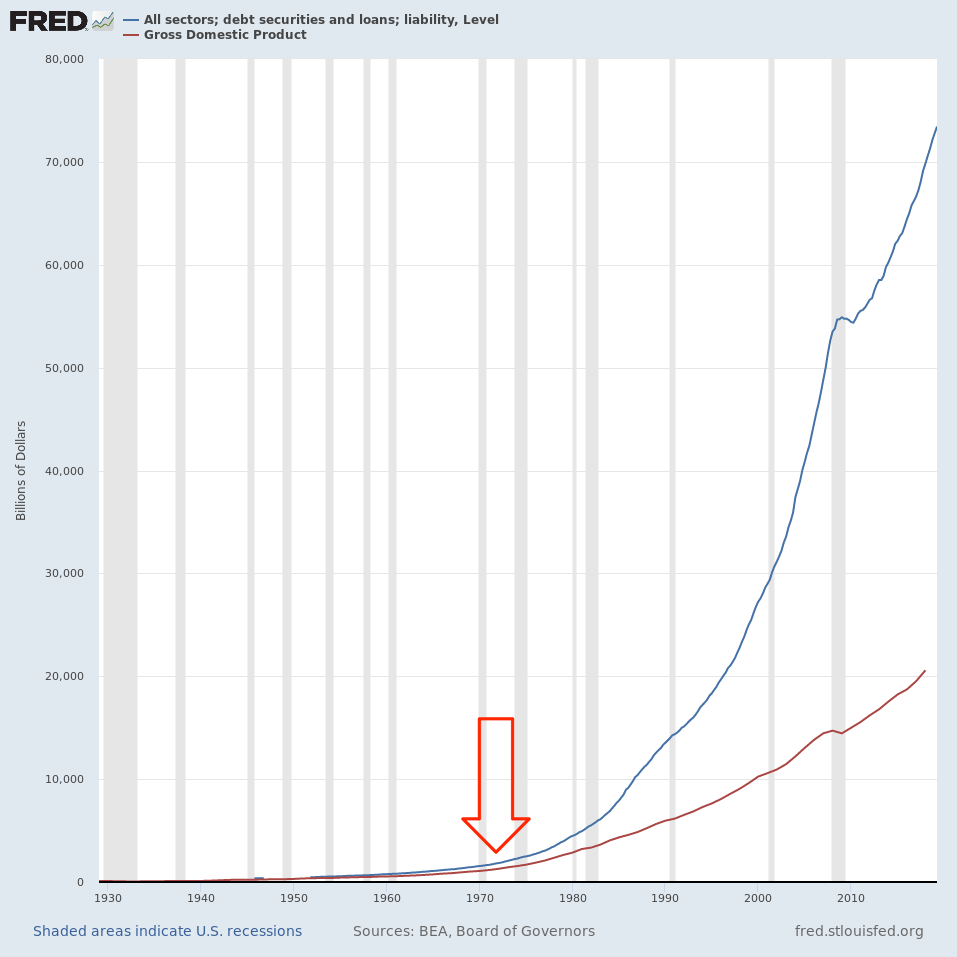

Debt issuance took off and outpaced both population and GDP growth after the world currencies were now tied to nothing. Governments could issue any amount of debt as long as they could find buyers that trusted their taxable base, and many buyers knew the circular life of debt issuance paid for by future debt issuance was a given.

I could go on for many more sections but this email has a length limit.

Where We Are Now

Few things have had larger implications on the world today than Zero Interest Rate Policy, or ZIRP, that followed the ending of Bretton Woods. Monetary bodies now had nothing holding them back from battling other monetary policymakers to find the fastest growth. I could not agree more with Ranjan Roy of The Margins that ZIRP has been the leading candidate for the “theory of everything” that explains much of today’s issues throughout economics, finance, equality, etc.:

The physics concept of a “theory of everything”:

“A hypothetical single, all-encompassing, coherent theoretical framework of physics that fully explains and links together all physical aspects of the universe.”

That's how I feel about ZIRP and all things business today. To understand why let's first talk about money.

Ranjan also eloquently explains the nth-level effects that free capital has had on today’s world as it naturally goes towards promised yield:

“So all these dollar-organisms all start swimming towards riskier waters. Treasury investors shift to corporate debt. Public equity hedge funds shift to late-stage private equity. Late-stage private equity shifts to mid-stage, mid-stage to early stage. Seed rounds become bigger. Angel investors become a thing. Unicorns, unicorns, and more unicorns.”

[…]

Then, for the companies that attracted the money had to spend it. Salaries inflate. Cultures change. Consumers are subsidized. Sure, some technology is created, but overall, nothing operates as it would without that thirsty capital. It changes the economics for competitors that do not welcome in the dollars. The second and third-order effects are difficult to comprehend.

Capital is a living organism and travels looking for food, or in its case, yield. As the supply of yield goes down due to lack of growth and natural expansion coming to an end, it becomes erratic. Hungry organisms become desperate and make irrational decisions when their brain runs low on fuel.

Venkatesh Rao has a similar take on it:

Weird things happen on the edge of system frameworks. Just like physical speed approaching the speed of light, distortions occur within capital as it approaches the yield of 0%. But, what is the natural, free-market rate of return? Rates imply growth, and as the entire globe becomes developed, population growth slows, and technological innovation solves the most visible and pressing issues, growth inherently will slow down. But, institutions are still solving for the 7-8% equity returns that have been assumed over the last century or so.

One of my favorite visualizations of this trend comes from the Bank of England’s working paper on 800 years of real interest rates:

Artificially lowering rates is meant to spur growth and up corporate and consumer spending and building, but it has had little effect since the financial crisis. The repercussions of ZIRP have scarred all consumers and are starting to distort economic theory.

It’s Time to Build, But Why Haven’t We Already?

Most people in the V.C. circles (echo chamber) have read Marc Andressen’s rallying cry amid the Covid epidemic. My question is, why haven’t we been building more already when 1) it is easier than ever to start a business, and 2) there is more cheap / free capital today than ever existed?

An interesting corollary is how the adoption of ZIRP has led “unicorn” companies to raise more money than ever before going public if they even go public at all. Arguably, it has never been easier to set up a company, establish an entity, publish a website, launch a store, and ship products or software. But, it seems companies have needed (maybe “been able to” is the more appropriate phrasing) to raise more capital than ever before.

Adjusting for inflation, Amazon raised ~$15M before going public in 1997, and Google raised $42M before its 2004 IPO. In Amazon’s case, it was a categorically heavier (and arguably harder with the logistics, scaling, etc.) business but raised a tiny amount of capital in comparison to today’s tech IPOs. Uber raised $24 billion, Airbnb has gotten $5.4B before its IPO initially set for this year, Instacart with $2.4B, Postmates with $903M, and the list continues.

Founders are giving away more and more of their companies as the cost of capital has gone to zero, all while it is easier than ever to start a scale a business.

Back to the main topic, why did Andressen need to even ring the bell on this crisis of entrepreneurial stagnation in the first place? The plea’s focus on the physical rather than the digital is in stark contrast when compared to his original writing around “Software is Eating The World”:

You see it in housing and the physical footprint of our cities. […] You see it in education. […] You see it in manufacturing. […] You see it in transportation.

It wasn’t always this way, though.

Tanner Greer of Scholar’s Stage wrote a percipient response to Andressen’s appeal in his On Cultures That Build post:

Yet this has not always been true. Patrick Collison has fun list of grand projects that went up "fast." As Collison notes, most of those things went up before 1960. Collison's list is focused on the physical: skycrapers, tunnels, ships, moon landings, military planes, and so forth.

Many people will immediately point to Silicon Valley and I agree that the Valley is a microcosm of what a building culture should look like from the outside. But why is that culture sitting alone on a peninsula in California? Why don’t Tulsa, Milwaukee, Little Rock, Lansing, and Omaha have the same mentality?

Hopefully, the now entirely accepted remote work world will allow these cities to catch up and become their own centers of builders.

Homework Reading

A couple of follow-up reads related Opus 6 on temporality:

Count off ten seconds. Now watch a clock. For many of us, there will be discrepancies. We should honor those—rather than correct them. A minute is only a minute under certain circumstances: contrast the minute spent waiting near your computer for bad news with the minutes spent in bed with your spouse or a hot stranger. We have divorced ourselves from the perceptual technics of time; while at the same time we are perhaps never more aware of it. This is the lesson of the pandemic: we are now obligated to playact the standardized time that capitalism demands of us, now without any of the external social trappings.

[…]

Wristwatches, our most personal, direct and dedicated link to objective time, are largely disappearing altogether. The ones that remain function as either jewelry, or as miniature extensions of smart phones, or perhaps most ironically, as retro affectations, signaling aesthetic sensibilities rooted in a different era. A mechanical pocket-watch can still tell you the current time, but it primarily tells you that the wearer is inhabiting, by choice, the nineteenth century.

I have been reading more and more of Edge’s content recently and their annual question for last year was a meta one:

"Ask 'The Last Question,' your last question, the question for which you will be remembered."

Due to the nature of Edge’s contributors, it is very overweight on theoretical physics and philosophy, but many questions make you think.

All of our time-wasting activities have seen an uptick in the Corona Era.

But if we see time and money as two sides of the same coin, then time spent not making money is wasted. Thus, our obsession with productivity has the pernicious side-effect of demonizing leisure. But only in leisure can we hear the birds chirping, feel the tingling warmth of a goodnight kiss, or listen to the echoes of the universe.

Framing The Conflict With China

Chris Balding provides a hawkish stance on China <> U.S. relations and chronic race. I am in general agreement with Balding here that there are fundamental differences in the governments, leaders, and, most importantly, cultures. I hold this opinion not as a result of loving America more than anything but because I have immense respect for the 2,000+ semi-continual reign of the Chinese culture.

The conflict has become more evident than ever with the Covid outbreak and differences in response by the two nations.

The conflict with China is not due to needing better communication or better understanding. Many have argued that due to Trump communication style, ending regular meetings, or lack of nuance the true failure lies with an inability to effectively communicate with China. This attributes to China a lack of intent about their actions rather than recognizing the reality that these actions and the larger framework within which they occur happens in a well planned manner to achieve specific objectives. The reality is that the policies that China is executing now have been planned and discussed clearly for years. Xinjiang, Taiwan, South China Sea, economic protectionism, Hong Kong, techno-authoritarianism these are clearly stated objectives by China across a variety of institutional formats.

Today’s Music

For this edition, I want to focus on small portions of songs that are some of the most beautiful measures of music in history:

I think the first 40 seconds of Dvorak’s E Major Serenade for Strings is some of the best music ever written.

Debussy’s Arabesque No. 1 - 0:20 - 0:45 are the most peaceful 25 seconds of music out there.

Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 - Most people know this piece from the aggressive start and famous middle section. But, I think the part starting at 5:25 is 1) technically incredible and 2) acoustically jaw-dropping.