Introduction

I recently moved to Switzerland after spending my entire life in the United States. Most of my time in America was spent growing up in suburban Wisconsin, which I consider to be home - at least in the sense that it is the place and culture that define who I am the most. I then spent four years attending college in Milwaukee and then five years living in New York City. While none of these periods are a lifetime, I think they are long enough to have a fair assessment of the life one can expect to live there. Of course, my life is singular to myself, but I like to think I observed the environment enough to have a fair view of the population’s general life.

Over the last couple of months, almost everyone in my life has asked some variation of the question, “What is it like living in Switzerland?” I am a long way from having a fully-baked answer to that. I haven’t experienced many things yet and can’t comment on - fully integrating into society, building our group of friends, seasons, holidays, taxes, child raising, etc.

Regardless, I thought I would share some initial observations by approaching it from a different angle. There is one thing that immediately hits you when you spend time in Switzerland: orderliness. On his great Questions page, John Collison phrases it a bit differently by asking, “Why are so many things so much nicer in Switzerland and Japan?” but I think “orderliness” is the best word to describe the feeling of day-to-day life in Switzerland. It is a really, really nice place to live and that fact is something you can feel right away.

Switzerland is unique in many ways and is famous, or infamous, for many things. People associate it with geopolitical neutrality and insularity. It is not part of NATO, not part of the EU, not on the Euro, and pledges its alliances very carefully. The Swiss people are notorious for not really caring about things happening elsewhere in the world. As long as things are ok in Switzerland, that is all that matters. This relates to the well-known bank secrecy laws that Switzerland mostly holds onto to protect bank clients, although some of these rules have been reversed in recent years due to the Russian / Ukraine war.

Switzerland has more Nobel Laureates per capita than any other country in the world and is continually ranked the most innovative country. ETH Zurich was home to Albert Einstein when he discovered the general theory of relativity. It has been ranked as the 2nd most economically complex country in the world behind Japan for 20 years which measures the diversity and complexity of a country’s economic drivers - sidenote: this link has one of the more interesting visualizations of country rankings over two decades, it is fascinating to see the decline of South Africa and Venezuela.

Switzerland is ranked 5th globally for life expectancy and the 7th healthiest overall. It is also regularly ranked in the top 10 happiest countries in the world.

Everything works and is on time in Switzerland. The Swiss government measures the punctuality of its trains to an almost mind-numbing level and proudly reports 93% punctuality of trains. It leads the world in terms of rail usage per capita, with the average Swiss person traveling 1,600 kilometers a year on the train, 60% more than the next country. It is home to the second-best road system (safety, quality, and density) in the world and 8th lowest car deaths per capita. It also has the most hiking trails per square kilometer, and its 65,000km of hiking trails nearly equal its 70,000km of roads.

Switzerland has the world's highest nominal GDP per capita (6th highest in PPP terms) if you ignore the capital haven / micro-economies, including Monaco, Bermuda, Luxembourg, and Lichenstein. It is estimated that 15%, or one out of every seven people, are net-worth millionaires in Switzerland. It is only second to Hong Kong and Singapore in billionaires per capita, although most of these, similar to HK and Singapore, are non-Swiss families that moved to Switzerland for tax reasons. The Swiss tax regime is very special. There are no capital gains taxes nor inheritance taxes for direct descendants or spouses - hence why so many wealthy families move here to pass down wealth or sell significant assets tax-free. Salary income taxes are roughly in line with the European average, although the highest tax bracket is nowhere near the Western EU countries’ 50+% marginal rate. Many Swiss cantons (the equivalent of States in the USA) levy a wealth tax on global assets held by a person and these rates are usually 0.1-1% / year on net worth.

Switzerland’s most interesting economic attribute is the size of the Swiss government in relation to its economy. In the average European country, government expenditure makes up 50% of the economic activity. France, Italy, and Belgium are the most extreme where 60% of their economic activity comes from the government. Generally speaking, the government’s involvement in the economy has risen everywhere around the world but this is especially true in Europe (shameless plug, but read my Imperium work if this phenomenon interests you.). Switzerland is once again an outlier in that the government accounts for only 31% of the economy. This figure has been flat for nearly 50 years. In Europe, it is only second to Ireland at 21% in this regard.

Fiscally, the Swiss government is the 5th least indebted federal government in the world. Central federal government debt to GDP currently stands at ~14%, only beaten by Norway (13%, explained by the sovereign fund), Tuvalu (7.5%, probably can’t even raise debt), Turkmenistan (5%, who knows if this is true), and Kuwait (2.9%, they have enough oil). Technically, the Kingdom of Brunei has only 2.5% public debt to GDP, the lowest in the world, but I refuse to include that as a legitimate government. These rankings change slightly when you include nonfederal government debt (state, municipal, etc.) but this is more difficult to compare given the differences in debt guarantees across various federal governments and how those ultimately flow down into the lower levels of government. Swiss cantons also have fairly strict indebtedness constraints, which limit their ability to run long-term deficits. The nonfederal level debt data is also a far more sparse database, so I don’t know how much I trust the reported data.

Other than bragging about our new home, why am I spending the time sharing all of this? I share it mainly because I want to understand why a small, landlocked country with no natural resources, vast cultural diversity, no military might, and plenty of other hindering attributes has achieved what so many societies aim to accomplish and still grows economically.

How do Growth and Order Relate?

The idea of orderliness is intangible, so it may be helpful to add some concrete examples. In my mind, an orderly society is one where you can rely on government services (energy, infrastructure construction, public works, etc) to function as you’d expect. Government officials don’t require bribes or favors to speed up or even get anything done at all. An orderly society is one where there is high trust between everyone in it and people subscribe to the fact that cooperation is a far better positive-sum strategy than corruption. An orderly society is one that is safe without extreme rates of crime or risk to your life.

Order in and of itself is not the most critical factor for everyone. Optimizing for it makes no sense for many governments in the developing world. They have more important things to work on, such as childhood mortality, food security, semi-functioning infrastructure, and other basic needs. A mother could not care less about daily order if her children are hungry. It is also fair to point out that wanting orderliness is a privileged thought in the first place. But, assuming those more critical prerequisites are all somewhat in place, then why does it appear that order and growth are mutually exclusive attributes? It would seem, at least academically, that an orderly society would be better set up to grow sustainably for longer than a disorderly one, all else being equal.

While an “Orderliness Index” does not exist, at least that I know of, one can imagine taking all the cultural, societal, governmental, and general attributes I listed above for Switzerland and ranking them for all countries. It is likely that if you plotted the orderliness of a country against its growth rate, an inverse relationship would emerge between the two. The slowest growing economies in today’s world (ignoring shocks such as war or revolt that cause sudden economic contraction) are also the most orderly - Finland, Austria, Ireland, New Zealand, Japan, Iceland, Netherlands, Italy, etc. Of course, all of these societies have issues, but the average person in the world would classify most of them as places with high-trust societies that function well day-to-day and that many of the 7 billion people in the world would like to call home if they could. The issue is that their economies don’t grow anymore, and many have contracted in recent years.

Conversely, the fastest growing economies - Niger, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Guyana, India, Rwanda, Ethiopia, etc. - are all not what most people would classify as orderly societies. I have traveled to some of these places and don’t claim to be an expert, nor do I have an intimate understanding of the day-to-day life of people there. But they do not exude a sense of order, high trust, functioning government services, trustworthy infrastructure, etc. Again, it is nearly impossible to pull apart all the governing factors of growth and development. These societies drastically differ in their population growth, demographics, cultural prioritization, immigration, productivity gains, government involvement, natural resource base (see Guyana as an extreme example), entrepreneurship, FDI, and countless other drivers that govern growth. It is fair to say that one thing they all generally lack is societal order.

An economy needs some very basic level of order to grow at all. Whether this be an authoritative order in the case of China or a more ground-level one like many economies in Southeast Asia, economic systems need some stability to grow reliably. Complete chaos and civil unrest, like we currently see in Sudan and Mali will never lead to economic expansion, regardless of the other factors at play. But it also seems, at least empirically, that too much orderliness leads or at least correlates with no growth.

What is the causal or correlative relationship between these two, if any? Can order naturally emerge or does it require institutions and coordination? Do economies begin slowing and does this shift people’s attention away from growth to quality of life and making things nice? Or does orderliness emerge from somewhere else, and does this cause economic growth to slow? Put very simply, why do all nice, orderly, and high-functioning societies stop growing?

Maybe if everything around you is pretty nice, then you may rethink what to do with that marginal hour of free time. Hustling for another dollar may not be the first thing that comes to mind. There is a clear cultural element here that is important to consider. The French and Italian cultures are notorious for prioritizing the joys of life more than the 40+ hour work week.

Then you have America where work is a central tenet of society. Compared to most Western Europeans, Americans work ~1-1.15 more hours per day according to the OECD. There are countless examples of the extreme work culture in America (120+ hour work weeks in finance, working on vacation, etc.) and this does lead to growth. America’s economy continues to surprise everyone with incredible growth at scale. With that in mind, I don’t know where I would plot American society on an “Orderliness Index” chart. When it comes to many of the qualities I shared above in the Swiss context, America ranks all over the place. It is a bastion for innovation on the one hand, but simultaneously has the worst public infrastructure in the Western / developed world. Its healthcare system has one of the worst ROIs in the world, yet it is still a destination for specialty care and innovative therapies. It is an unbelievably wealthy country, but America’s wealth inequality is comparable to Haiti, Cameroon, Bolivia, and Uganda. The safest cities in the United States, as measured by homicide rate (San Jose, San Diego, and El Paso, have around 4 homicides per 100K people), all have higher homicide rates than the most dangerous regions of Europe. Yet, America’s economy grows. This relationship between order, or lack thereof, and growth emerges again.

How Can We Have Both?

Returning to Switzerland, it once again provides a unique situation. The country is the most orderly by almost any measure one can think of. Yet, it is still growing at a respectable pace. Over the last decade, the Swiss economy grew a cumulative 21.6%, or approximately 1.8% per annum in real GDP terms, beating out every other Western EU country by an average of 50 basis points a year in GDP growth. Growth of 1.8% per annum is by no means rapid growth but it is the long-term growth goal of many countries. This achievement is even more surprising when you consider that in that same period Switzerland was already one of, if not the, wealthiest countries in the world. In a region of slowing growth, Switzerland continues to buck the trend even while already being at the top of the ranks.

Again, it is impossible to pull everything apart and understand at a granular level what factors drive this equilibrium of order and growth. I don’t know any laws of nature forbidding other countries and societies from achieving both simultaneously. I don’t have the answers as to how it can be done. Instead, I will leave you with more questions:

How vital is societal trust in creating more orderliness? Bryan Caplan touches on this a bit in his writing and Nassim Taleb’s quote rings true here: “I am, at the federal level, libertarian; at the state level, Republican; at the local level, Democrat; and at the family and friends level, a socialist. If that saying doesn’t convince you of the fatuousness of left vs. right labels, nothing will.”

How much of a role do institutions, government or otherwise, play in forming societal order? In the developing markets, do you need some CCP-esque authority to force order onto a society?

In this age of revolt, degrowth mentality, institutional distrust, and slowing global economies, should we give up on order and prioritize economic growth above all else?

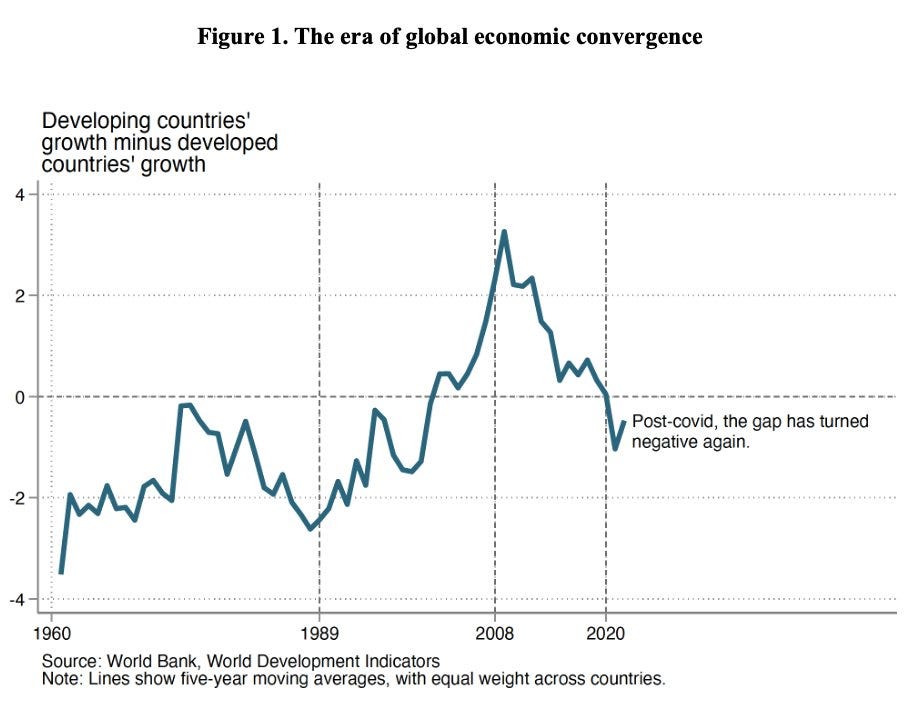

For the first time in many decades, the developing world is beginning to grow at a slower pace than the developed world. Does this throw the whole hypothesis out the window? Maybe order has nothing to do with it at all:

Derek, I know where you heard it all first...lol. Great summary of a really special place. Also, it is "Mali," not "Mal,i" unless there is some glottal stop I have always missed.